Trump’s ‘Garden of American Heroes’ is a monument to celebrity and achievement – paid for with humanities funding that benefits everyday Americans

- Donald Trump’s “Garden of American Heroes” project aims to commission 250 statues of famous Americans from a predetermined list, funded by humanities grants that benefit everyday Americans.

- The list includes recognizable figures like Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, and Harriet Tubman, as well as celebrities like John Wayne and Julia Child, but excludes many notable historical and cultural figures.

- The project reflects Trump’s “great man” theory of history, which attributes major events to the actions of influential individuals, while ignoring broader social, economic, and cultural forces.

- However, this approach comes at a cost: funds previously allocated to tell stories about lesser-known historical and archival projects have been slashed by 85%, potentially leading to untold stories going unrecorded.

- The project’s focus on celebrating popular figures raises questions about the representation of everyday Americans in American history, with some arguing that it reinforces a top-down approach to U.S. history that neglects the experiences of ordinary people.

Donald Trump first came up with his plan for a “National Garden of American Heroes” at the end of his first term, before President Joe Biden quietly tabled it upon replacing Trump in the White House.

Now, with Trump back in the Oval Office – and with the country’s 250th anniversary fast approaching – the project is back. The National Endowment for the Humanities is seeking to commission 250 statues of famous Americans from a predetermined list, to be displayed at a location yet to be determined.

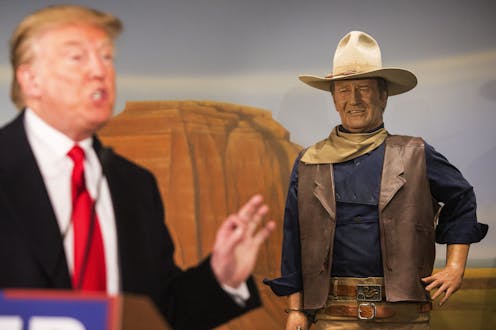

It isn’t clear who compiled the list of 250 to be honored. It includes names that are largely recognizable and whose accomplishments are well-known: politicians like Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy; jurists Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia; activists such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harriet Tubman; celebrities such as John Wayne and Julia Child; and sports stars like Kobe Bryant and Babe Ruth.

The statue garden coincides with an executive order from March 2025 in which the Trump administration denounced what it saw as historical revisionism that had recast the country’s “unparalleled legacy of advancing liberty, individual rights, and human happiness.” Instead, it had constructed a story of the nation that portrayed it “as inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed,” which “fosters a sense of national shame.”

“We don’t need to overemphasize the negative,” explained Lindsey Halligan, a 35-year-old insurance lawyer who is named in the order as one of the people tasked with reforming museums that receive government funds.

Trump often casts himself as a man of the people. But as historians, we don’t see a garden of heroes as a populist effort. To us, it represents a top-down approach to U.S. history, akin to the hagiography that Americans already regularly get from movies, television and professional sports.

And it comes at a cost: It’s going to be paid for with funds that had been previously allotted to tell stories about people and places that may be less familiar than the proposed figures for Trump’s garden. But they’re nonetheless meaningful to countless communities across the nation.

Only the movers and shakers matter

Trump’s fixation on America’s luminaries is adjacent to the “great man” theory of history.

In 1840, Scottish philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle published “On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History,” in which he argued that “The History of the world is but the Biography of great men.”

American biologist and eugenicist Frederick Adams Woods embraced the great man theory in his 1913 work, “The Influence of Monarchs: Steps in a New Science of History.” In it, he investigated 386 rulers in Western Europe from the 12th century until the French Revolution. He proposed a scientific measurement to quantify the relative impact these rulers had on the course of civilization.

Then and now, many other historians and sociologists have pushed back, arguing that the “Great Man” view of history oversimplifies the past by attributing major historical events to the actions of a few influential individuals, while ignoring broader social, economic and cultural forces.

Nonetheless, it continues to have broad appeal. It’s very popular among corporate leaders, for example, many of whom like to portray themselves as visionaries, with their business successes proof of their genius.

Trump’s garden of heroes reflects his penchant for celebrating wealth, champions and successes, akin to what Walt Disney tried to capture with his Disney World ride Carousel of Progress, which highlights American technological advances.

A national redundancy?

However, the U.S. already has a national statuary hall, which opened in the U.S. Capitol in 1870. Each state has contributed two statues; for example, Massachusetts honors Samuel Adams and John Winthrop, while Ohio celebrates James Garfield and Thomas Edison.

Today there are 102 statutes, though just 14 women.

Importantly, the roster is fluid – not set in stone – and reflects debates over whom the nation ought to celebrate.

Over time, the representation has become slightly more inclusive. The first woman, Illinois educator Frances Willard, was added in 1905. Only in 2022 did a Black American appear, when educator Mary Bethune replaced a Confederate general from Florida. And in 2024, Johnny Cash replaced James Paul Clarke, a former governor and senator from Arkansas with Confederate sympathies.

Kent Nishimura/Getty Images

What about everyday Americans?

We don’t think there’s anything wrong with celebrating and honoring popular figures in American history. But we do think there’s an issue when it comes at the expense of other historical and archival projects.

The New York Times reported that US$34 million for the project would come from funds formerly allocated to the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities, whose budget has been cut by 85%.

Many of the grants that have been slashed explore, celebrate and preserve history in ways that stand in stark contrast to a statue garden. They involve, as Gal Beckerman writes in the Atlantic, efforts that “are about asking questions, about uncovering hidden or overlooked experiences, about closely examining texts or adding to the public record.”

They include one that supports the digitization of local newspapers and archival records; another to collect and preserve oral histories of local communities; a grant that funds the production of documentaries and podcasts about local communities; traveling exhibitions that bring items from the Smithsonian’s collection to small towns and rural areas; and a grant to fund the collection of first-person accounts of Native Americans who attended U.S. government-run boarding schools.

These and countless similar history projects serve millions of people far from Washington, and they have broad support from lawmakers and citizens of all political stripes.

In 1938, as forces of fascism gathered in Europe, a Connecticut high school social science teacher said, “The greatest need of America, on the threshold of the greatest epoch of its history, is citizens who understand the past out of which the nation has grown. … Let us look into the souls of the leaders and the common people who have made America great.”

In his 2016 campaign, Trump promised to work on behalf of everyday Americans – the “forgotten man and woman.” But the proposed statue garden of famous figures cuts out the common people from America’s story – not just as subjects of history, but as its stewards for future generations.

With funds slashed from organizations dedicated to local history, we wonder how many more stories will go untold.

![]()

Jennifer Tucker has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities for research that examines the social and cultural role of modern technology, such as facial recognition, through a historical lens.

Peter Rutland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.