The Panama Canal’s other conflict: Water security for the population and the global economy

The Panama Canal is one of the most important waterways in the world, with about 7% of global trade passing through. It also relies heavily on rainfall. Without enough freshwater flowing in, the canal’s locks can’t raise and lower ships traveling between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Droughts mean fewer ships per day, and that can quickly affect Panama’s finances and economies around the world.

But the same freshwater is also essential for Panama’s many other needs, including drinking water for about 2 million Panamanians, use by Indigenous people and farmers in the watershed, as well as hydropower.

When the region experiences droughts, as it did in 2023-2024, the resulting water shortages can lead to increasing water conflicts.

One of those conflicts involves a new dam the Panama Canal Authority plans to begin building in 2027. It would be designed to secure enough water to keep the canal, which contributes about 4.2% to the country’s gross domestic product,, operating into the future, but it would also submerge farming communities and displace over 2,000 people from their homes.

AP Photo/Matias Delacroix

This recent drought wasn’t an anomaly. As an academic who studies the effects of rising temperatures on water availability and sea level rise, I’m aware that as the climate warms, Panama will likely face more extremes, both long dry spells and also periods of too much rain. That will force more trade-offs between residential needs and the canal over water use.

Complex engineering remade the landscape

The Panama Canal was built over a century ago at the narrowest point of the country and in the heart of its population center. The route was historically used by the Spanish colonies and later for a rail line between the oceans.

The idea of a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans began as a French endeavor, led by architect Ferdinand D. Lesseps, designer of the Suez Canal in Egypt. After the French effort failed, the U.S. government signed a treaty with newly independent Panama in 1903 to take over the project.

The U.S. acquired the rights to build and operate the Panama Canal in exchange for US$10 million and annual payments of $250,000. Later, the Torrijos-Carter Treaty in 1977 committed the U.S. to transfer the control of operations to Panama at the end of 1999.

The canal project was designed to take advantage of the region’s tropical climate and abundant average rainfall.

It harnessed the water of the Chagres River basin to run three sets of locks – chambers that, filled with fresh water, act like elevators, lifting or lowering ships to compensate for the difference in water levels between the two oceans.

To ensure enough water would be available for the locks, the canal’s designers changed the shapes of the region’s mountains and rivers to create a large watershed – over 1,325 square miles (3,435 square kilometers) – that drains toward the canal’s human-made lakes, Gatun and Alajuela.

About 65% of the water that flows from the watershed today goes to operate the locks. The majority of that water is quickly lost to the oceans.

Even the two newest locks, built in 2016, only reuse about 60% of water on each transit – 40% is flushed to avoid saltwater from the oceans intruding into the watershed.

Threats to water security

Panama’s wet tropical weather is predominantly influenced by its location near the equator, the trade winds and the oceans. Most of its rain falls during the wet season, from May to November. However, weather records show a drop in average precipitation starting around 1950.

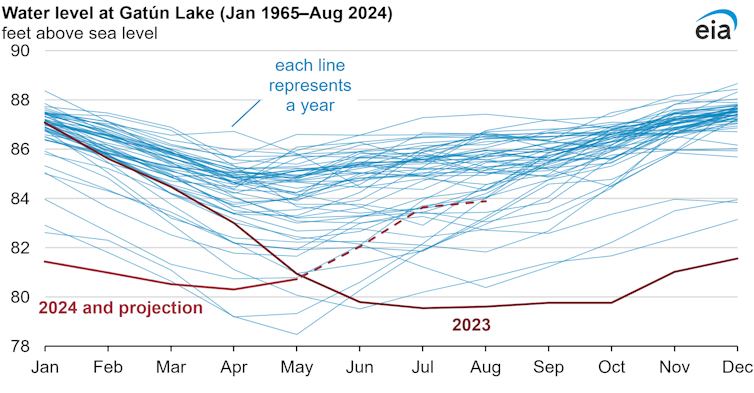

The driest years resulted in dangerously low water levels in Gatun Lake that made canal operations difficult, including in 1998, 2016 and most recently 2023-2024. El Niño weather patterns can mean particularly low rainfall.

EIA

In December 2023, the Panama Canal Authority was forced to limit the number of daily transits to 22, compared with 36 to 38 usual crossings, because too little freshwater was available.

To avoid steep financial losses, the Panama Canal Authority raised prices and auctioned transit opportunities to the highest bidders. Without those measures, the authority estimated it would lose $100 million a month from reduced ship traffic because of the water shortage.

Ecosystems also need enough water, and changes in forest tree composition have become evident on Barro Colorado Island in Gatun Lake in response to rising temperatures and more frequent droughts.

Climate change is also creating greater variability in rainfall. Too much rain can also be a problem for canal operations. In December 2010, the biggest storm on record caused landslides and $150 million in damage that interrupted transits on the canal.

Sustaining Panama’s canal and its people

Temporary measures for saving water have been already implemented. The Panama Canal Authority shortened the chamber size in some of its locks to use less water for smaller vessels and minimized direction changes.

In January 2025, the authority approved plans to build the new dam on the Indio River to increase water available for the canal. The dam could solve some water concerns during drier periods for the canal.

However, it also illustrates the country’s water conflicts. Once filled, the dam’s reservoir will submerge over 1,200 homes by some counts, and more people in the region will lose access to land and travel routes. The Panama Canal Authority promises that residents will be relocated, but some of those living in the region fear they will lose their livelihoods, along with the communities their families have lived in for generations.

AP Photo/Matias Delacroix

Residents across Panama, meanwhile, regularly hear media campaigns that encourage them to save water. An Environmental Economic Incentives Program promotes forest conservation and sustainable family agriculture to conserve water resources.

The Panama Canal is a crucial part of international trade, and it will face more periods of water stress. I believe responding to those future changes, as well as market and societal demands, will require innovative solutions that respect ecosystem limits and the needs of the population.

![]()

Karina Garcia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.